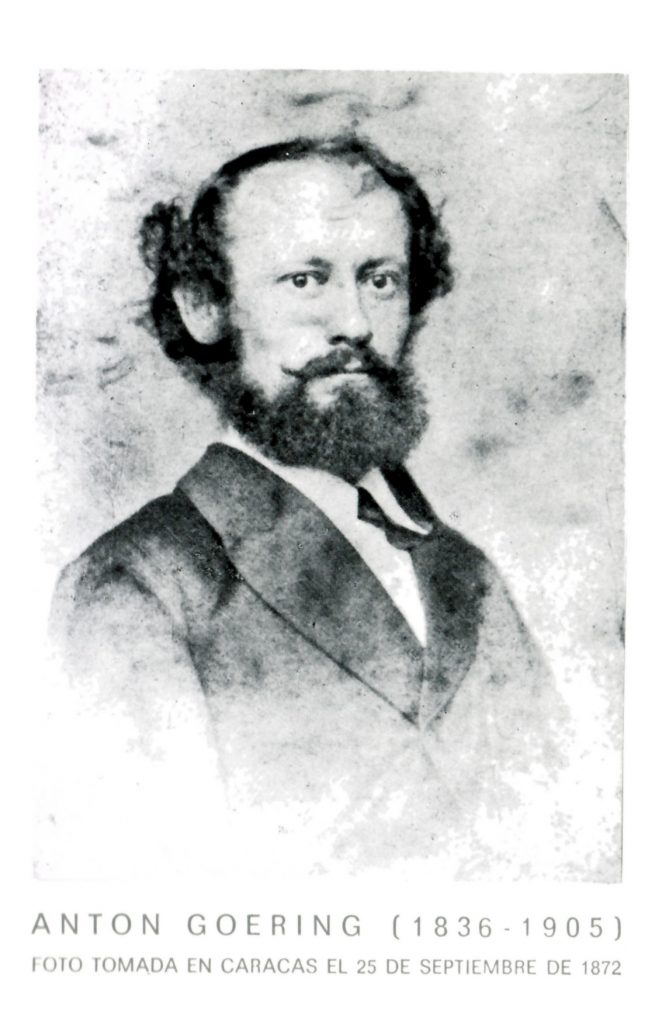

Although Christian Anton Goering (1836-1905) was the son of a craftsman he succeeded in a career as an explorer, painter and animal preparator. Like Humboldt before he went on two expeditions to South America (1856 and 1866) and conducted botanical and geographic studies.

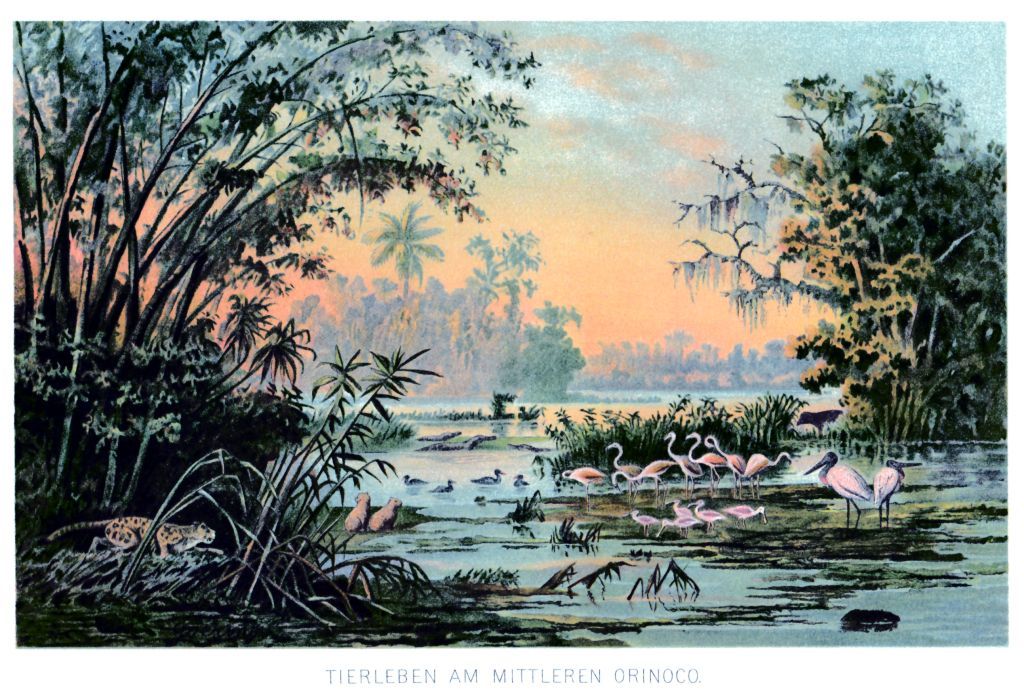

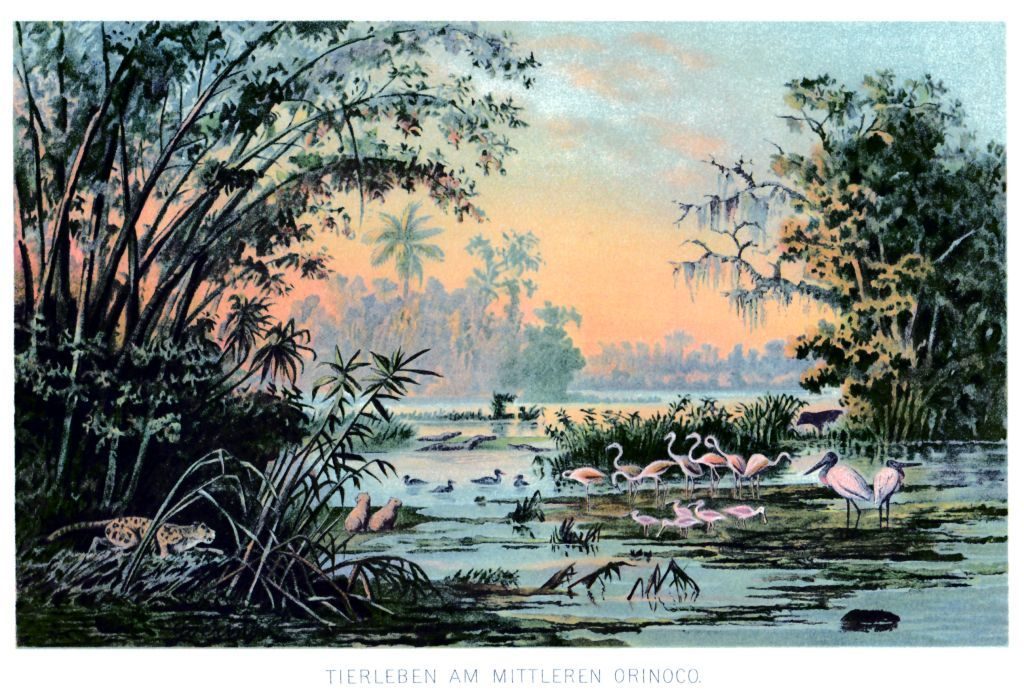

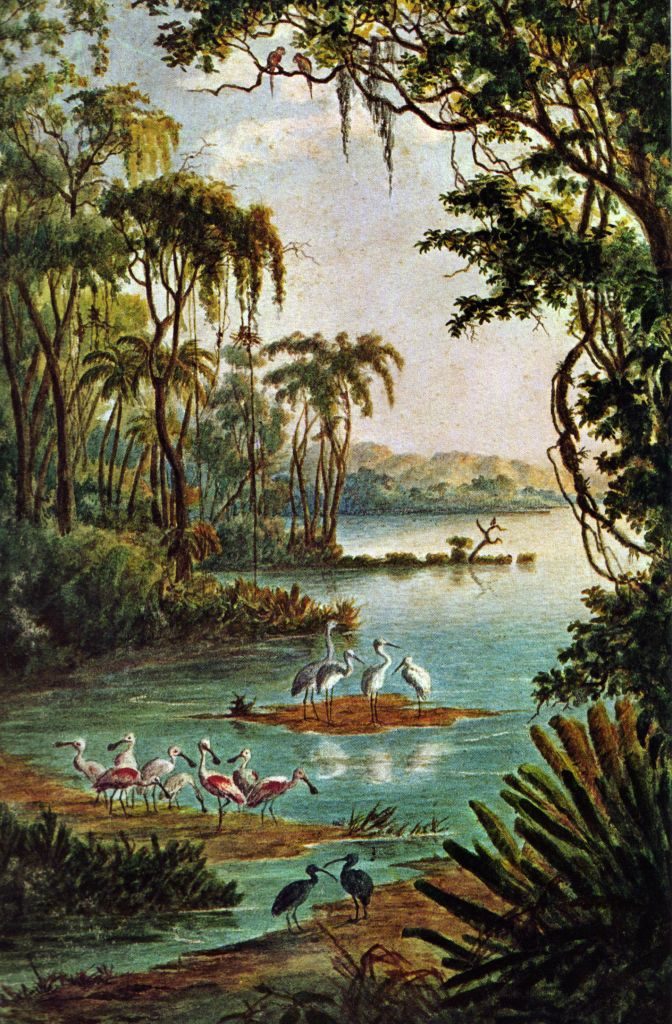

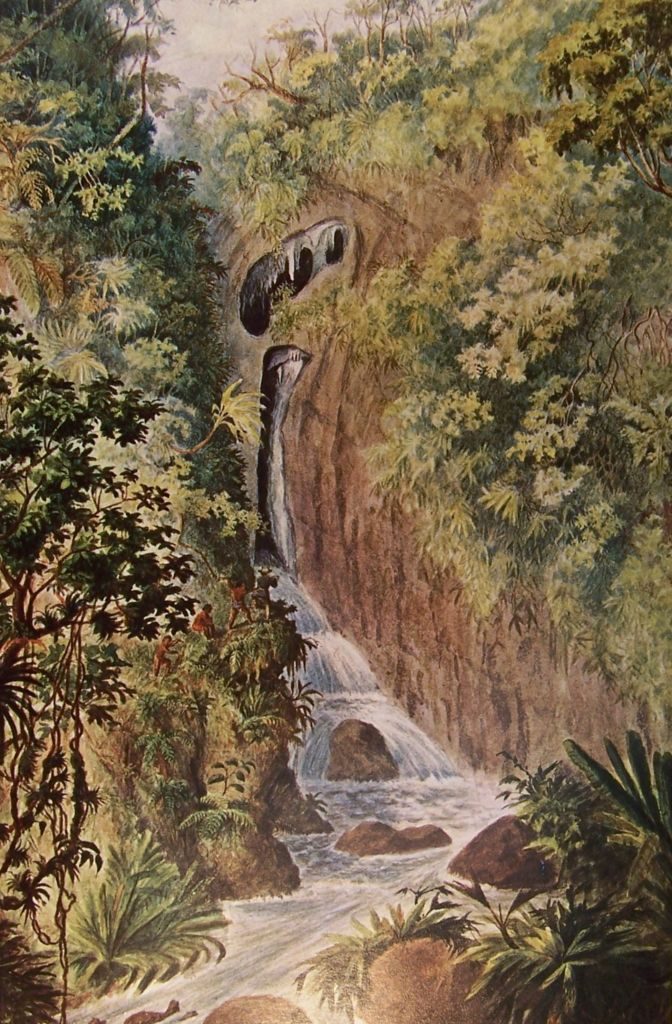

On his first journey he worked as assistant and companion of the well-known german scientist Hermann Burmeister. On the second one Goering ventured on behalf of the Zoological Society of London. He collected rare animals for the collection of the Natural History Museum, did preparations and captured his impressions of the landscape in pictures, painted in watercolor. With his work, Anton Goering made an important contribution to the study of Venezuela. Amongst other things, he discovered the up to then unknown caves at Caripe. In 1893 he published his travel impressions in Leipzig under the title: „Vom tropischen Tieflande zum ewigen Schnee, Eine malerische Schilderung des schönsten Tropenlandes Venezuela“.

Anton Goering and his way to South America

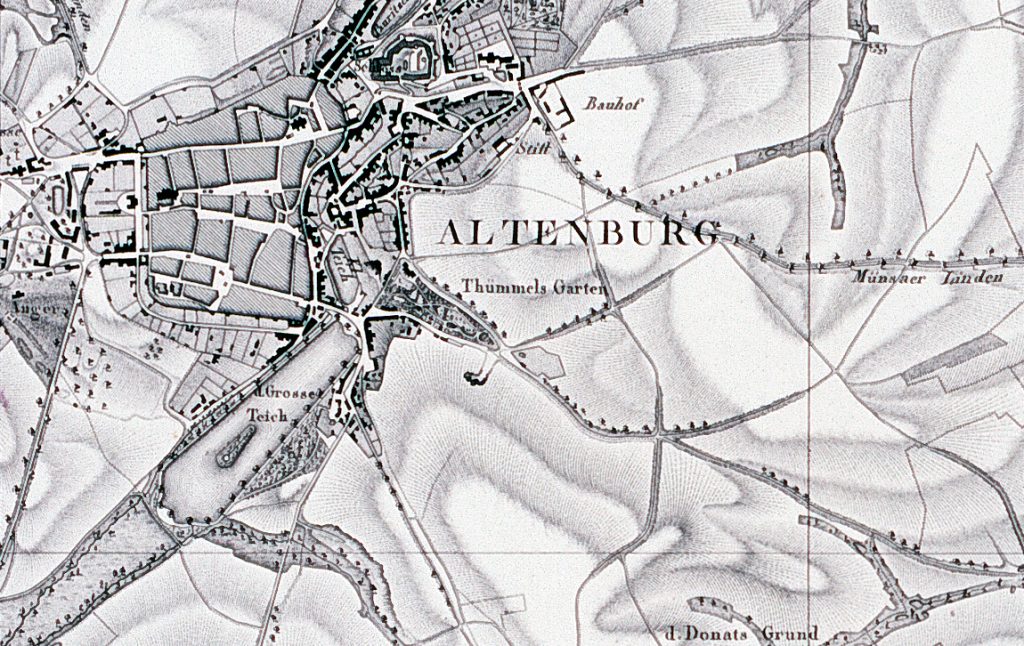

Christian Anton Goering was born on 18. September 1836 in Schönhaide in today’s Altenburger Land. His father, a craftsman, was a member of the regional society for ornithology and so his son, too, found his interest for nature. He studied in the school of arts of Bernhard von Lindenau in Altenburg, 20 kilometres from Schönhaide. Later he worked as preparator and conservator in the zoological museum of the University of Halle. His professor was Dr. Hermann Burmeister. Amongst others Christian Ludwig Brehm, and his son Alfred Brehm gave Goering natural scientific advice.

The first expedition to South America (1856-1858)

Anton Goering gained his first travel experiences as a companion of Hermann Burmeister. For over two years they explored the flora and fauna of Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay.

In September 1856 Goering traveled from Halle to Hamburg, where he met with Burmeister and his son. Goering and the young Burmeister left Hamburg on the sailing ship “Dorothea” on September 29 with the destination Rio de Janeiro. Hermann Burmeister, the leader of the expedition, took another ship. After almost six weeks they reached the coast of South America.

On December 1, 1856, the journey started in Rio de Janeiro. Over two years the group traveled to Montevideo, San José, and Mercedes. In 1858 Goering took a ship back to Germany.

The second expedition to South America (1856-1858)

Through his patron Philip Lutly Sclater, secretary of the Zoological Society of London, Anton Goering got the opportunity to take a field trip to South America as a corresponding member of the Zoological Society of London, in 1866.

His main destination was Venezuela, where he collected bird skins for the British Museum (Natural History Museum) and explored the country’s flora.

On September 18, 1866, he left London on a steamship and reached the port of Carupano (via Trinidad) on September 30. For eight years, Anton Goering researched and painted the landscape and the flora and fauna of Venezuela. He discovered the up to then unknown caves at Caripe and sent collected bird and animal skins to the British Museum.

In 1868 Dr. Sclater published Goerings collections in an article in the journal “Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London“. A first collection contained 173 skins, collected at Carupano, Pilar, and Caraccas. Three of the birds were described as being probably new to science. A second collection contained specimens of 99 species, the most of them Venezuelan birds.

In 1874 Goering left South America and took a ship back to Germany.

Later, in 1893, Anton Goering published his travel impressions of this secondexpedition to Venezuela in his book: „Vom tropischen Tieflande zum ewigen Schnee, Eine malerische Schilderung des schönsten Tropenlandes Venezuela“.

The later years

Since 1874 Goering worked as an animal and landscape painter in Leipzig. Together with other artists, he made the illustrations for “Brehms Tierleben” (Brehm’s Animal Life).

He remained in contact with the Altenburg naturalists for life. So he was appointed an honorary member of the “Naturforschende Gesellschaft des Osterlandes zu Altenburg” and the Ornithological Society of Leipzig. Duke Ernst I. of Saxony-Altenburg awarded him the title of Professor for his services. Anton Goering died on December 7, 1905, in Leipzig.

By Franziska Engemann / Museum Burg Posterstein

In 2019 we celebrated the 250th birthday of Alexander von Humboldt. The well-known scientist and researcher inspired not only his contemporaries to do traveling and researching all over the world, but also later generations until today. That’s why we prepared an exhibition on Anton Goering (1836-1905).

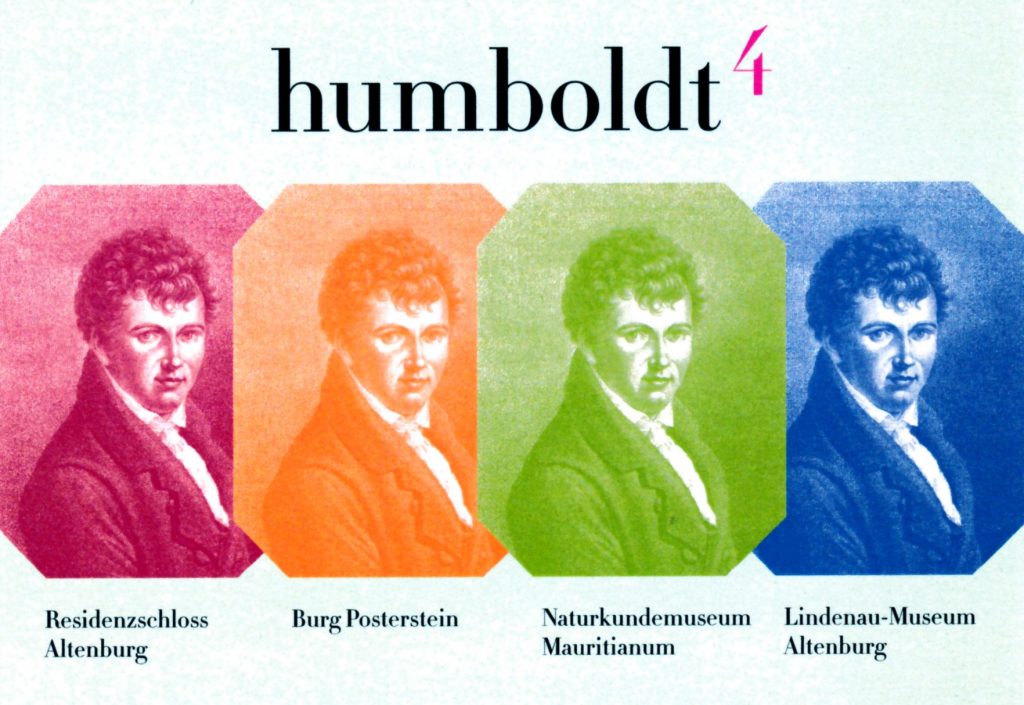

For this event four museums of the county Altenburger Land in Thuringia, Germany – Lindenau-Museum Altenburg, Residence castle Altenburg, Museum of Natural Science Mauritianum and Museum Burg Posterstein – presented special exhibitions about Humboldt and his influence on the region together under the title: #humboldt4.

In Museum Posterstein Castle we commemorated the illustrator Christian Anton Goering (1836-1905).

The exhibition at Museum Posterstein Castle followed Goering’s progress and life from Altenburger Land, Germany, to South America. His journeys are revived in his diaries and woodcuts, loans from the Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography in Leipzig (Leibniz Instituts für Länderkunde). Exotic animals prepared by Anton Goering put a picture of the research expeditions in the footsteps of Alexander von Humboldt across to the visitors.