A special part of the permanent exhibition of Museum Posterstein Castle tells the story of the minister Hans Wilhelm von Thümmel (1744-1824). This remarkable man was a friend oft he Duchess Anna Dorothea of Courland (1761-1821) and regular guest at her castles in Löbichau and Tannenfeld. Here we present Hans Wilhelm von Thümmels gardens.

A special part of the permanent exhibition of Museum Posterstein Castle tells the story of the minister Hans Wilhelm von Thümmel (1744-1824). This remarkable man was a friend oft he Duchess Anna Dorothea of Courland (1761-1821) and regular guest at her castles in Löbichau and Tannenfeld. Here we present Hans Wilhelm von Thümmels gardens.

As head of goverment Hans Wilhelm von Thümmel was one oft he most famous persons in the Altenburg part of the duchy Saxony-Gotha-Altenburg. And a minister close to nature. As a confidant of the Gotha Dukes, he represented the duchy as a diplomat in Paris, Berlin, Vienna and Denmark. He initiated the geodetic surveying of the duchy and left behind a comprehensive landscape heritage. But often it did not last.

Hans Wilhelm von Thümmel, minister in the duchy Saxony, Gotha and Altenburg (Museum Burg Posterstein)

His harmony with nature can be guessed not only at his extraordinary and beautiful tomb: the 1000-year-old oak in Nöbdenitz. It can be guessed at his horticultural heritage: for example Thümmel’s private English garden with a palace in Altenburg, his manors in Nöbdenitz and Untschen, the “Polish cottage” in Münsa, or the palace garden in Altenburg.

These gardens were not only seen as places of recreation and entertainment in the countryside, but also as educational establishment: as gardens of the Enlightenment.

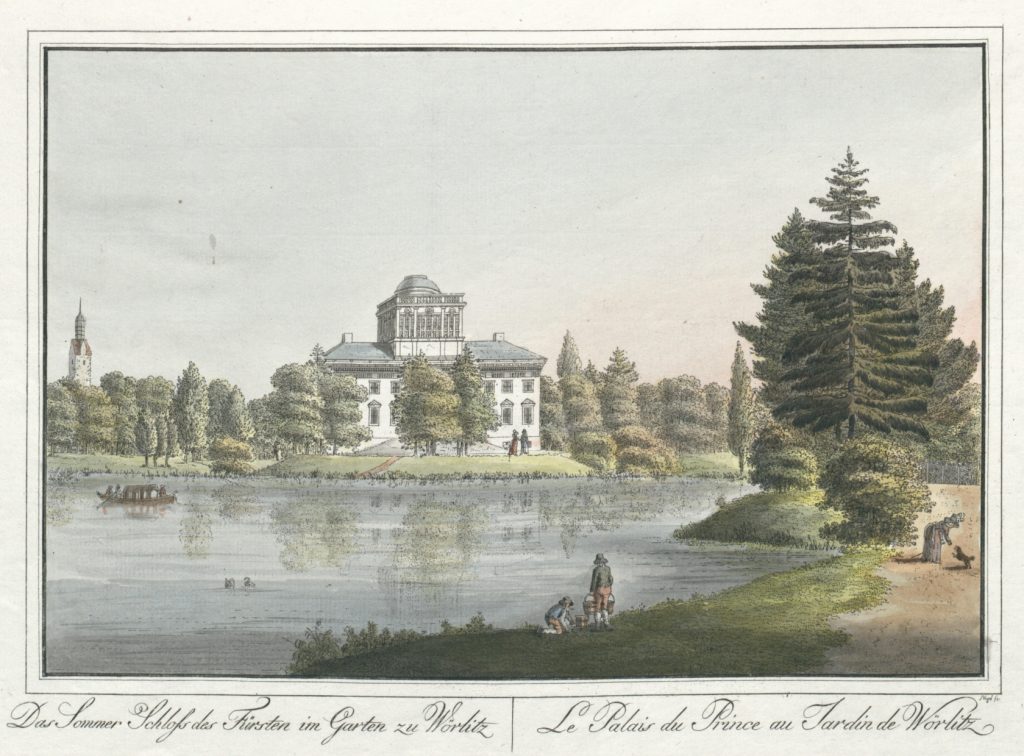

Le Palais du Prince au Jardin de Wörlitz | Nagel, Johann Friedrich (Public Domain, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek).

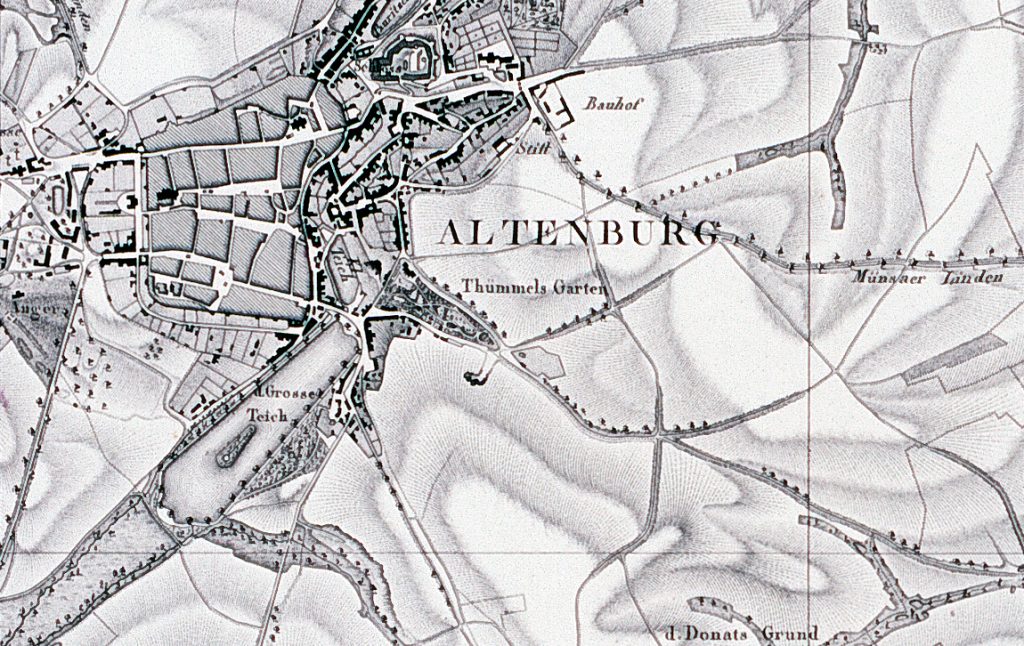

Thümmel’s private English garden in Altenburg

At the beginning of the 19th century, the garden of Hans Wilhelm von Thümmel was considered as one of the most important sights of Altenburg. In its final extension, the long park ground was enclosed by a wall with seven gates. At the highest point of the site, with the best view of Altenburg, Thümmel had a villa built in 1788 in the style of Italian classicism.

The park had artificial grottoes, streams and ponds. Small pleasure houses in different styles as well as the so-called „Kachelhaus“ – or „Turkish Pavilion“ – were integrated into the concept. The well-known artist Adrian Zingg captured the beauty of the Thümmel garden for eternity in his pictures.

Thümmel’s garden in Altenburg on the Thümmel map from 1813, section VIII.

As Thümmels legacy the garden did not last long. Several decades after his death in 1824 the garden had been greatly reduced by Thümmels heirs by selling several areas. Today, only the preserved central building of the palace reminds of its former glory.

The palace garden in Altenburg

In addition to the design of his private garden in Altenburg Hans Wilhelm von Thümmel was also involved in the transformation of the palace park Altenburg from baroque to landscaped grounds.According to reports of the Altenburger Chronicler Christian Friedrich Schadewitz (1779-1847), the chamber president Thümmel had already 1784/86 removed yew tree figures as well as the hedged. The open spaces were laid out with grass and a new orangery was placed on it. Around 1800, the first tulip trees were planted and formed the foundation for today’s English Park of Altenburg Castle.

Nöbdenitz manor – Thümmels old-age residence

Hans Wilhelm von Thümmel came into the possession of the manors Nöbdenitz and Untschen by marriage.Especially the park around the estate Nöbdenitz with its romantic hermitage met with universal approval. In 1782, Thümmel’s father-in-law and predecessor in office, Johann von Rothkirch und Trach (1710-1782), had the old Nöbdenitz castle renovated and a new mansion built, as well as a mausoleum as family grave. Thümmel chose this peaceful place as his old-age residence.

For sailing on the pond of Nöbdenitz manor

Nöbdenitz is very close to the castles Löbichau and Tannenfeld, in which the duchess Anna Dorothea of Courland invited guests to her well-known salon. But also visits by the Duchess and her guests in Nöbdenitz at Thümmels house were usual events. Here they met to sail on the large pond of the manor and took walks to the 1000-year-old oak, which Thümmel had chosen as his future grave.

Castle and manor house in Nöbdenitz – Hans Wilhelm von Thümmel had an english garden (lithografie: Museum Burg Posterstein).

The surrounding park extended east of the 1782 built „New Manor House“ whose perron led down to the garden. A little brook – the “millrace” – flowed through the park. Figures or rondels had been placed at partings of the way. From the main way three bridges led over the millrace into the landscape on the south side, which was enclosed by a wood. A hermitage had been built next to the weir at the millrace. It was a popular motif in the gardens of the Enlightenment. The hermitage was a quiet place of contemplation amidst nature, a place where one be able to communicate with oneself, nature and God. This hermitage in Nöbdenitz was also pictured by the engraver Zingg. The building itself doesn’t exist anymore.

A „Chinese bathhouse“ and a „Polish cottage“

Also the redesign of Untschen manor including the establishment of a bathhouse in the Chinese style or the creation of the destination „Polish cottage“ in Münsa were realized under Thümmels direction. But he was not the only one who appreciated and promoted the local garden art. The much-admired duchess Anna Dorothea of Courland, also belonged to this circle.

The english garden in Tannenfeld in spring 2018.

Tannenfeld – pleasure garden in the English style

Contemporaneous with the building of Tannenfeld Castle also the development of Tannenfeld park started under the direction of the Duchess of Courland. The new building, with a beautiful view to Posterstein Castle, was embedded in the new landscape park. At the time of Anna Dorothea of Courland Tannenfeld was about half an hour away from Löbichau.

Tannenfeld Castle in spring 2018 (Foto: Marlene Hofmann):

If the visitors turned from the main road between Ronneburg and Schmölln to Tannenfeld, they passed a small gatehouse and through an alley lined with Italian poplars they came to park and castle. Sandy paths led the walkers past groups of trees or shrubs and sentimental-romantic memorial stones. One stone was bearing the inscription “Peterswiese” and reminded of the 1800 deceased husband of Dorothea of Courland. A narrow stream flowed through the meadow and ended in a pond. On an island in the pond there was the so-called „Hermitage“, a grotto formed of rocks.

By Franziska Engemann, Christiane Nienhold und Marlene Hofmann, translation: Franziska Engemann, Matthias Huberti / Museum Burg Posterstein